Three Paths

Finding Inspiration in Academia

In this new series on academic development, we focus on some of Khyentse Foundation’s longer-term projects. Here, we take a look at the Doctoral Student Support program.

In this new series on academic development, we focus on some of Khyentse Foundation’s longer-term projects. Here, we take a look at the Doctoral Student Support program.

A young French art enthusiast born into a family of atheists; a Chinese former villager raised in a Buddhist family; a Tibetan lama who grew up in rural Kham: how did these three—from very different backgrounds—all find their way to being awarded a Khyentse Foundation Doctoral Student Support grant?

KF’s Academic Development Committee launched the KF Doctoral Student Support program in 2020 to address a significant gap, one that often left students unable to complete their doctoral degree or with insurmountable debt. The issue had come to light through the committee’s work of supporting universities around the world. Unlike the existing PhD Scholarship program, which is open to the public, KF partnered with eight different universities to identify the most promising PhD candidates at their institutions. Since the Doctoral Student Support program’s inception 19 students have been selected to receive a grant, and each has a unique story to tell.

Here are three such stories.

Elodie Pascal – From Art Enthusiast to Buddhist Research Scholar

As a young girl, Elodie was already fascinated by art. She was raised by atheist parents with a scientific background, whose perspective was to allow their children to choose their own path, especially regarding education, career, and spiritual matters. Elodie’s interests at that time did not include science; instead, she enrolled in undergraduate studies specializing in Japanese and Chinese arts, including Buddhist architecture and sculpture, and then a master’s degree at the École du Louvre in Paris. “I was intrigued by non-European cultures, especially Asian ones,” she says. “I never felt anything special while looking at Catholic images—the endless numbers of Madonnas that we had to study for the Renaissance arts classes truly bored me. However, in front of the peaceful Buddhas, the angry guardian gods, and the mummified monks, I felt—and still feel—a wide array of emotions.”

Elodie had been planning to study Japanese paintings and scrolls for her master’s degree, but in the first year was obliged to select one of the research topics proposed by a curator. One of the options was dry lacquer Buddhist statues in Japan. “Fate had spoken,” she says. Freer to choose her research topic for the second year of the master’s, she stayed on course and decided to investigate three Buddha sculptures from the Musée Guimet.

The second year of the master’s program was a decisive one: Elodie could choose to become a curator in France, spending years preparing for the difficult exam and most likely ending up working for a museum with no connection to Asian art; or to pursue the path of research, requiring proficiency in both spoken and written Japanese. For this, she would need to embark on another undergraduate degree, this time in Japanese language and civilization. “I knew how arduous it would be to start a new degree at 25 … but the excitement was also present,” she says. A transformative internship in American museums at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign during this year enlightened her as to the differences between American and French institutions, and one of the teachers she met there also helped her gain clarity. The decision was made: Upon completion of her master’s she was accepted at Inalco in Paris and received her BA in Japanese studies in 2018.

Following the BA, a year spent in Kyoto, Japan’s ancient capital, deepened Elodie’s understanding of the country and its culture. She visited temples, shrines, and sacred mountains. “Contemplating in person all these sacred icons that I had been studying, exploring temples impregnated with the smell of incense, and attending rituals—everything strengthened my passion for Buddhist art,” she says. She started looking for a PhD research topic that went beyond art history and involved rituals and lived beliefs. Through reading, her curiosity was triggered by the topic of zōnai nōnyūhin, or “objects encapsulated within Buddhist sculptures”—articles and texts embedded in statues—and she looked for a suitable program.

Hearing about the KF Doctoral Student Support program being offered at the University of Edinburgh, she applied and was successful, and is now a student under the supervision of Prof. Halle O’Neal, a noted scholar in premodern Japanese Buddhist art. The KF grant also helped her win a Nippon Foundation scholarship to attend an immersive language study program in Japan for a year. She is currently in her third year at Edinburgh and is already making major contributions to our understanding of Buddhist life, art, and practice in medieval Japan.

Xiaoqiang Alex Meng – From Village Practitioner to Globetrotting Student

Asked why he is studying academic Buddhism, Alex replies, “Because I was raised by Buddhists.” His response’s simplicity belies the complex and key role his family played in his embarking on a Buddhist path—a journey of both personal and academic discovery.

Born into a Buddhist family in a poor rural village outside of Shaoxing, a historical city in Zhejiang Province, eastern China, Alex spent his childhood immersed in local religion and folklore—a wild, fantastic world of fairies, ghosts, spirits, mysterious animals, Daoist immortals, Jesus, and bodhisattvas. In that world, his grandparents served as semi-Buddhist ritualists who played a specific role in the village. One day, when Alex was around 6, a ceremony was held to install some statues in a small Buddhist-Daoist shrine behind his house. The statues included one of the deity Wenquxing, the “Star of Literature”—a god responsible for overseeing literary pursuits and examinations. As the statues were passed over the heads of the assembled villagers, some incense ash fell and burned Alex’s right hand. He did not cry out, however; instead, he frowned at the fresh wound and swallowed his tears. From then on, the idea that Alex was special was cemented in the minds of the villagers and his grandmother, who also believed the burn was a blessing from Wenquxing, ensuring that he would get good grades in school. His establishment as a young village practitioner, and perhaps later as a scholar, can be traced to that day.

Alex went on to complete both an undergraduate degree in history and a master’s in Sanskrit and Tibetan in China, and hoped to continue on as a PhD student. One day, while working on his master’s thesis, he learned that Prof. Jonathan A. Silk from Leiden University was recruiting for the KF Doctoral Student Support program. Alex applied, never imagining that he would be successful, and to his astonishment, was ultimately chosen to receive the grant.

Alex arrived in the Netherlands in 2020, but due to the Pandemic his new life in Leiden only really began in spring 2022. Along with learning Dutch and other languages, he attended seminars, visited scholars and friends, published research papers, applied for summer schools, did field research, gave talks at workshops and conferences, taught a course at the university, and exchanged with other academic institutions.

Alex is extremely grateful for the opportunities the KF Doctoral Student Support program has given him, including the monthly lectures and in-person workshops of the Khyentse Foundation Buddhist Studies Lecture Series based at Northwestern University. “I can get to know some amazing fellow PhD students who are also supported by KF and studying worldwide,” he says. “This really makes my lonely and sober academic life brighter and happier!”

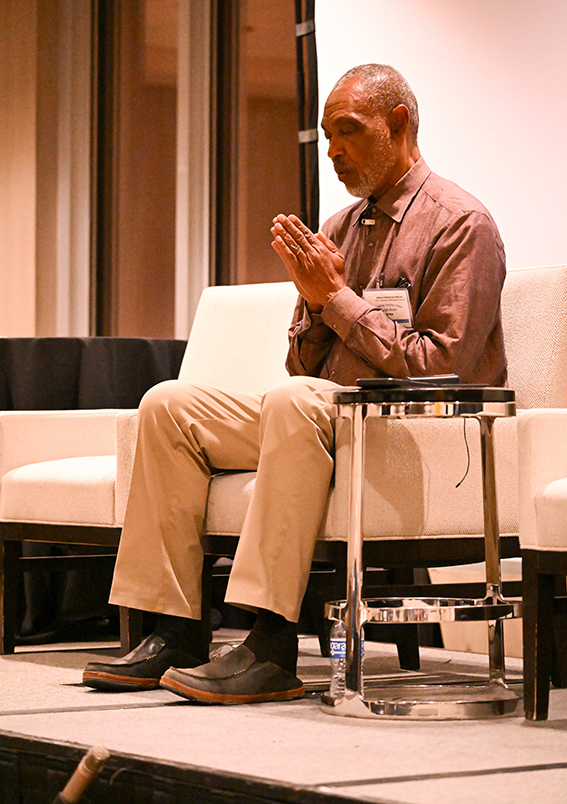

Khenpo Yeshi – From Disadvantaged Schoolboy to Traveling Teacher

Yeshi, as he was called as a boy, grew up in Nakchu (Naqu), a nomadic region of rural Kham, in conditions of extreme scarcity. Against his parents’ objections, he insisted on attending school—one of only two children in his village to do so. The seasonal school was a 2-hour walk each way over a mountain pass and through a charnel ground that was surrounded by 8-foot-high walls built from stacked skulls. Yeshi eventually became the student of the village lama, who taught him about tantric funerary rites.

Finding his way to Lhasa and from there to India and Nepal, for the next 10 years Yeshi studied at various Gelug, Nyingma, and Drikung Kagyu monastic colleges, receiving his Khenpo designation from Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling Monastery in Nepal. He also completed a 3-year retreat under Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. However, he had long dreamed of pursuing Buddhist studies at a Western academic institution, and after being invited to the US post-9/11 for an important puja, he was able to enroll at De Anza College in Cupertino, California, and then finished his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in religious studies at UC Berkeley. Today, he is a doctoral candidate at UC Berkeley, focusing on the early history of the Dzogchen Nyingtik tradition. He also travels regularly as a Buddhist teacher.

“His itinerancy has produced an astonishingly broad education across both the Buddhist monastic and Western academic worlds,” writes Prof. Jake Dalton of UC Berkeley about Khenpo Yeshi. “He is a true intellectual who has devoted his life to learning and teaching.”

Khenpo has now spent 2–3 years studying the two earliest collections of Nyingtik writings, with the goal of producing a dissertation on the status of the ground (Tib. gzhi) in 11th- to 14th-century Dzogchen. He hopes his dissertation will be helpful for practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism as well as of interest to academics.

Featured image above: Khenpo Yeshi presenting at the Khyentse Foundation Buddhist Studies Lecture Series workshop, Northwestern University, May 2024. Photo by Sarah H. Jacoby.